Do our voices matter?

In recent years, rising student activism in our district and surrounding area has seen the results of incredible change. Last year, we fought to keep our 8-period schedule with student involvement and parent encouragement; nationally, in 2018, we walked out in solidarity with students across the nation after the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida. In the last month, students of Kennedy Catholic High School protested the firing of two teachers on account of their sexual orientation. But is this activism worth it? Are our voices actually heard?

March 21, 2020

“But why should I care? My voice doesn’t matter, anyway.”

Every time these questions come up in conversation, I can feel myself wanting to roll my eyes. I’ve heard this argument time and time again: students don’t believe they have the ability to effect change, and so they stop caring.

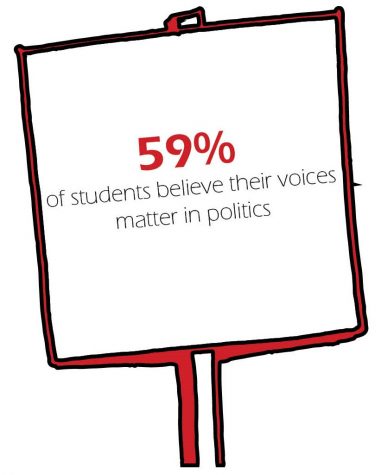

Our government is based on the ideals of democracy. It relies on the public to elect officials, guide policy, and share beliefs to better society. Younger generations, unfortunately, do not participate to the extent that they once did. In part, decreasing political efficacy is to blame.

Our government is based on the ideals of democracy. It relies on the public to elect officials, guide policy, and share beliefs to better society. Younger generations, unfortunately, do not participate to the extent that they once did. In part, decreasing political efficacy is to blame.

“Within a community setting, the longer that people go without believing their voice matters, the more true that becomes,” senior Tatum Tomlinson said. “It’s really important that you do believe your voice matters. You never know how you can impact your community.”

Americans who don’t believe their voice matters won’t actively pursue an issue they care about. This phenomenon of learned helplessness has consequences beyond our personal lives; if issues don’t receive attention in the news, there won’t be any discussion.

“If you look at the issues that the candidates talk about, with the exception of Sanders’ free college, they’re not speaking to the issues that 18 to 24 year olds are dealing with,” social studies teacher Amy Cooke said.

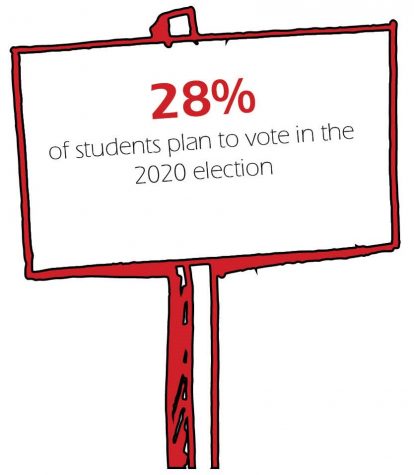

So it seems like effecting change only happens when we participate. But because only a quarter of Liberty students can actually vote in the upcoming presidential election, does that mean three-fourths of the school can’t speak up for what they believe in?

So it seems like effecting change only happens when we participate. But because only a quarter of Liberty students can actually vote in the upcoming presidential election, does that mean three-fourths of the school can’t speak up for what they believe in?

“Students can be heard in any political activity, like when students at Kennedy Catholic High School walked out,” Cooke said. “I really do think student voice matters in that way. But until kids come together with a common voice for a common cause, people tend not to listen to them.”

High schools and universities have traditionally been the foundation of change. Harkening back to the 1960s, in the era of civil rights and the Vietnam War, Southern racial integration began in Little Rock Central High School. Mary Beth Tinker’s decision to wear a black armband in school cemented students’ freedom to free speech in public schools. In March 2018, students at Liberty walked out in their own protest to draw attention to the issue of gun control after the school shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida.

“I didn’t make the choice to talk until I went out there,” Tomlinson said. “I felt that it was necessary for someone to say something so that the decision to walkout could be made into a meaningful experience.”

Tomlinson, who brought one purple flower for each victim of the Parkland shooting, addressed a rapt audience of students during the designated walkout time. She was able to use her voice as a fifteen-year-old high school student to speak out on an issue she deeply cared about.

“I really appreciated that discussion that I had with some of the students that participated in the gun walkout because I could understand where they were coming from,” principal Sean Martin said. “I am proud of our students for how they handled that. They took responsibility for missing their classes and handled themselves with respect and peace.”

Sometimes, however, walkouts are more than a school-sanctioned activity. Traditionally, they have been a major element of civil disobedience, which encourages breaking laws in a peaceful manner to draw attention to a political issue. Martin Luther King Jr. especially relied on civil disobedience to achieve his ends, as his illegal sit-ins disrupted normal life and drew media coverage.

For students in high school, there aren’t many repercussions for civil disobedience—for Tomlinson, any sacrifice is inconsequential in the long run.

For students in high school, there aren’t many repercussions for civil disobedience—for Tomlinson, any sacrifice is inconsequential in the long run.

“Walkouts are worth the consequences in the greater scheme of us developing as people. It’s much more important to experience standing up for what is correct. Liberty is a safe environment to take that hit of having an unexcused absence to practice standing up for what you believe in,” Tomlinson said.

Alternatives to walkouts are equally as valuable, if not as dramatic.

“There might be ways that are more lasting than just a walkout,” Martin said. “There are ways to make a point that could allow people to still be in class but also make their point and be very vocal.”

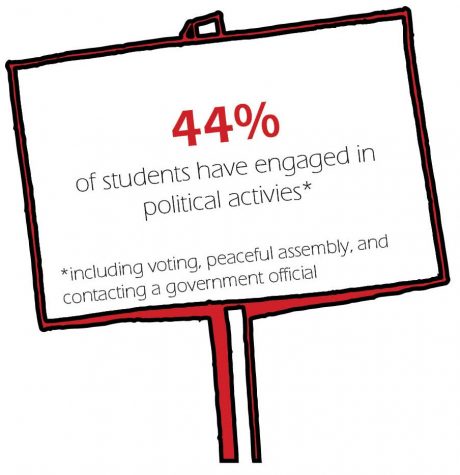

Social media platforms—one of those ways to make a point—allow for easy, public communication around social issues. Many students, including those who cannot vote, utilize Twitter, Reddit, and the YouTube comment section to discuss politics that affect their daily lives.

“I’m a part of JSA,” junior Declan Stratford said. “I have a strong belief that what I believe in is true, and I want to stick up for it.”

JSA, or Junior States of America, is another method of expressing political views. As a school-sanctioned club, JSA provides a safe space to investigate for oneself the values and beliefs held by different parties.

The club is also an open forum for discussion and debate, which Martin believes should be the first step in political participation encouraged by schools.

“We want students to make their own decisions and take positions on issues by analyzing thoughtfully and thoroughly,” Martin said. “Our responsibility is to help our students develop those skills of critical thinking and patience.”

Even just general information in class can provide assistance in shaping our beliefs and building our critical thinking skills. History reminds us of our past and our mistakes as a society; English explores thematic topics of racial discrimination and sexism within novels; fun electives like Economics, Statistics, and Psychology show the many facets of humans, and look at general trends in our world.

“The best thing that we as a school can do is have students understand issues and then come to their own opinions,” Martin said.

Academic courses are fantastic for understanding issues, but oftentimes, students don’t have the opportunity to discuss between themselves solutions to national or world problems. That’s why organizations like JSA and Model United Nations exist. Even for students not of voting age, clubs are a great way to increase both political participation and political knowledge.

Academic courses are fantastic for understanding issues, but oftentimes, students don’t have the opportunity to discuss between themselves solutions to national or world problems. That’s why organizations like JSA and Model United Nations exist. Even for students not of voting age, clubs are a great way to increase both political participation and political knowledge.

“I talk to other people about political issues in JSA and try to convince my friend group to talk about different things,” Stratford said. “My voice matters in the fact that I can sway other people’s opinions.”

Academia and politics don’t always have to be separate.

“Political participation also gives an opportunity for teachers to bring political activism into the classroom and talk about it throughout the day. That conversation can be more valuable when teachers decide to participate in the academic setting,” Tomlinson said.

The most important thing, however, is to believe that your voice matters, and to commit to fighting for issues that matter to you, regardless of pushback from peers, parents, or persons of authority.

“We need to be more supportive of students using their voice, even if it’s standing up against school policy or district leaders,” Cooke said. “So often, your age group—high school students—are so trusting of adults, thinking that we know what’s right. We’re not any different than you all.”