Bridging the generational gap

We’ve seen it on Reddit. We’ve heard it on TikTok. Gee, we’ve even heard it from government officials. “OK, Boomer”, a minimalist clapback increasingly used by millennials and Gen Z-ers to dismiss baby boomers as old-fashioned and out of touch with current issues, seems to have conquered the internet. It’s a trendy thing to say, but that’s the problem. When did we become okay with reducing intergenerational dialogue to a mere catchphrase?

January 21, 2020

Myths and Truths

I only had to look at the web’s most searched questions about each age cohort to get a sense of what people think of one another. When I typed “why are boomers” into the search bar, the auto-complete options included “to blame,” “so salty,” and “so entitled.” People also look up why millennials are “failing,” “such babies,” and “obsessed with food.”

Then I came across the worst of it all: “why Gen Z is screwed.”

Reliance on technology seems to have a lot to do with this perception.

“When the electricity goes out and internet becomes unavailable, doing homework becomes problematic for my kids,” social studies teacher Steve Darnell said. “I say to them, ‘Why didn’t you print it off?’ I always have a hard copy. I grew up in that generation.”

“When the electricity goes out and internet becomes unavailable, doing homework becomes problematic for my kids,” social studies teacher Steve Darnell said. “I say to them, ‘Why didn’t you print it off?’ I always have a hard copy. I grew up in that generation.”

Born after 1996, Gen Z-ers are “technology natives,” as ASB advisor Michelle Munson put it. They never grew up without mobile devices designed to make life as convenient as possible, raising concerns for some that they don’t know the value of hard work.

“There’s a stereotype that Gen Z is lazy and that they lack resilience and grit. The reality is that grit and resilience looks very different to them than to boomers and Gen X,” Munson said.

Even if Gen Z-ers are actually as slothful as they are made out to be, at least they are the most informed of sloths.

“Technology enables us to communicate and get information from around the world, which was much harder in earlier times,” junior Allyson Mangus said.

Most notably, the modern ease of access to information has resulted in the alliance between younger generations around the world in climate change activism, sometimes against older generations. “Kids think that we’re all baby boomers and that we destroyed the whole world with climate change,” Munson said.

Munson believes that such prejudices arise because large age gaps discourage mutual understanding. “What a baby boomer is to me is very different than what a baby boomer is to younger generations. Because my parents were baby boomers, I am closer to that generation,” she said.

What, then, do baby boomers and Gen X really think about climate change? There must be a reason for the judgments laid against them.

“Boomers and Gen X are not raised to be global citizens. We didn’t have the same access to information that millennials and Gen Z do,” Munson said.

“Boomers and Gen X are not raised to be global citizens. We didn’t have the same access to information that millennials and Gen Z do,” Munson said.

Darnell offers a different take: false alarmism in the past makes older generations cautious, more so than the younger generations, when deciding what “research” can be trusted.

“When I was young, there were claims that television is going to lead to an increase in violence and lower literacy,” he said. “Today, there are some scientists claiming that in twelve years, we’re going to be beyond the point of return to save our environment.”

Experience has taught baby boomers and Gen X to examine recent findings with a more critical lens, but some misinterpret this as an irrational indifference to current issues. “It’s simply ludicrous to assume that older people do not support a healthy environment,” Darnell said.

Reaching Mutual Understanding

With so many generational differences, how can we possibly distinguish what’s real from what’s perceived?

English teacher Bhumi Dalia suggests that we begin with an understanding of the nature of our prejudices. “Stereotypes originate from some truths,” she said, “but to generalize them to everyone is dangerous.”

For example, it is a fundamental truth that the prevailing attitudes of any time period are often heavily influenced by its respective contemporary events. When misinterpreted, however, this fact could easily turn into an accusation that the older generations live in the past, holding onto views characterized by events that are no longer relevant.

For example, it is a fundamental truth that the prevailing attitudes of any time period are often heavily influenced by its respective contemporary events. When misinterpreted, however, this fact could easily turn into an accusation that the older generations live in the past, holding onto views characterized by events that are no longer relevant.

Mangus warns against jumping to such a groundless conclusion. “Everyone has a chance to experience right now. Just because a person grew up in the twentieth century doesn’t mean they don’t know anything about the twenty-first century,” she said.

Unfortunately, dispelling generational misperceptions is no easy task because the stereotypes have found a niche in mainstream media, ranging from “OK, Boomer” hashtags and memes to full-fledged articles expressing one generation’s criticism of another.

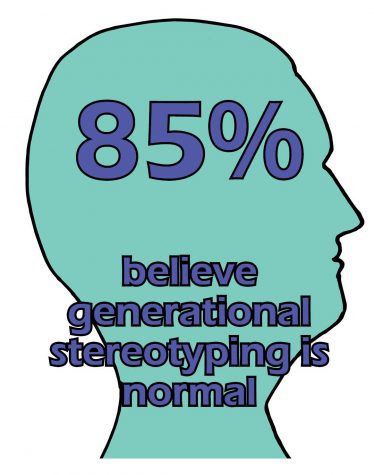

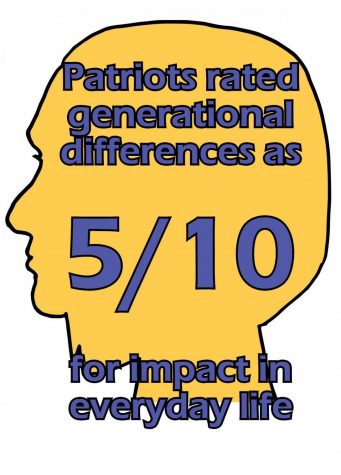

Social studies teacher Wes Benjamin believes that generational stereotyping is exasperated by the increased influence of the media but that it is not at all a new phenomenon. He told me: “When I was your age, I could probably say that people who were older didn’t understand me. 25 years from now, you’re going to have people that are going to say things to you similar to what boomers are getting now.”

It seems as though the younger and older generations will never be satisfied with one another, but Darnell sees that as a sign of striving for progress.

“There’s a constant effort to reflect on our differences as the torches pass from one group of power in positions of power to a younger group of people coming into positions of power,” Darnell said. “Young people want to identify what is wrong before leaving their nest. There are things that they want to do differently.”

As humans, we are very quick to judge, but Munson believes that it is possible to acknowledge our differences without having to view one generation as superior or inferior to another.

“We’ve got to be open-minded so that we can meet others where they are and see them for who they are,” she said.

According to Dalia, our differences lie not in our core values, but in how we prioritize and express them. “One person’s prioritization of one value becomes the point of contention, and that leads to miscommunication and perpetuation of stereotypes,” she said.

According to Dalia, our differences lie not in our core values, but in how we prioritize and express them. “One person’s prioritization of one value becomes the point of contention, and that leads to miscommunication and perpetuation of stereotypes,” she said.

If we have the option of referencing our shared values as we work out our differences, then why should there be any reason for the so-called generation war being waged between younger and older people?

“It’s because nobody in the conversation is willing to change their perceptions of others in a different generation,” Dalia said.

On that note, I’m afraid we are in great danger of recreating the generation version of Pride and Prejudice if we don’t make an honest attempt to correct our misunderstandings of one another.

Let us, then, take Dalia’s words for it when she says progress only comes as a result of thoughtful and meaningful dialogue.