You’re living in a mob

They’re screaming. The room’s dark, chairs circled. Your best friend’s sobbing. The mob is shouting curses, throwing objects, hating a faceless figure. For now, you stand alone, observing. The urge to join in is almost uncontrollable, but you’re fearing something greater. We might not be in Orwell’s 1984, and this isn’t sophomore English class. But when the Two Minutes Hate comes on, will you resist its pull?

Just a few weeks ago, a TOLO poster by an Issaquah High School student went viral. “If I was black,” the poster read, “I’d be picking cotton. But instead I pick you. TOLO?”

What happened next may very well have come straight out of Orwell’s nightmares. Students, parents, and complete strangers alike took to Twitter, hurling insults and even death threats at a seventeen-year-old high school student. Eventually, the minor’s name was leaked.

“That’s the nature of the beast with Twitter,” math teacher Thomas Kennedy said. “The danger of going viral is huge.”

Social studies teacher Peter Kurtz agrees. “The internet is the bread and circuses of the modern age.” he said. “It’s just really sad.”

However, not everyone feels as if the attention she received was unwarranted.

Issaquah High School senior Engu Fontama decided to host an unsanctioned school walk-out on April 3, just a few days after the poster went viral. Over 300 Issaquah students attended, even drawing the attention of local news organizations.

“It was necessary for Issaquah High School students to take charge of the rhetoric surrounding our school and racism,” Fontama said. “The student didn’t make a mistake, but committed an offensive and thoughtless action for which she deserves to suffer the consequences.”

“It was necessary for Issaquah High School students to take charge of the rhetoric surrounding our school and racism,” Fontama said. “The student didn’t make a mistake, but committed an offensive and thoughtless action for which she deserves to suffer the consequences.”

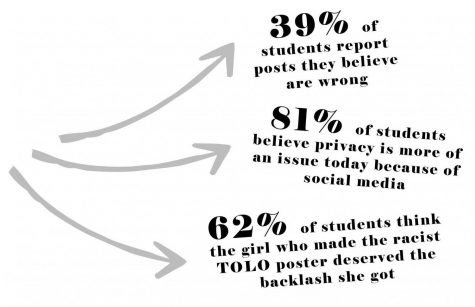

62 percent of Liberty students also believe that the student deserved the overall response she got.

“While I don’t believe that threatening violence is okay, if you take time out of your day to be hateful and post disgusting, hateful things like disgusting, hateful posters,” junior Elise Sickinger said, “you should expect that there might be backlash against you.”

What’s the drive behing this backlash? Kennedy believes the culprit is our own mob mentality.

“It’s something Twitter really inspires, to look at what this horrible person did even though a bunch of other horrible people did the same thing,” he said.

He relates this to the recent college admissions scandal.

“Lori Loughlin went viral, even though there were 85 people indicted,” Kennedy said. “Of course it’s a woman actress and her daughter who get flamed for doing this, because they are newsworthy.”

Junior Max Moye goes as far as to compare social media to lynching, in terms of how personal the attacks are.

“The media can pick up on it,” he said. “If you wanted to ruin someone’s reputation, social media would be the best way to do it nowadays,” he said.

Perhaps because of this understanding, Moye didn’t make as big a deal about the poster. “Every kid makes stupid mistakes,” he said. “It’s wrong to demonize people because they made some silly joke as a kid.”

So, beyond just avoiding death threats, how can we ensure that our personal responses to issues are appropriate and not incited by peer pressure?

In the case of the TOLO poster, junior Tatum Tomlinson believes that the emphasis should have been placed on solving the issue instead of the attacking the student.

“It’s important to come out and say that it was wrong, as a person, as a school, as a district,” she said. “But the attention she got was hateful and just as destructive as the hateful poster.”

“All too often, we emphasize what we see as the problem rather than solutions,” Kurtz agreed. “Would Martin Luther King Jr. have emphasized how bad the student was for making a mistake, or would he have emphasized how the family handled it?” he asked.

Kurtz makes a good point. While news of the TOLO poster spread quickly, the apology letters issued from both the student and the student’s family had nowhere near as large of an impact. If we do not acknowledge growth, how can we hope to continue growing?

Even if we may not be the ones sending death threats, we each have a responsibility to step out of the circle. We need to be sure that each action we take is inspired not by peer pressure, but by hope for the future.

It will be difficult, but it will also be worth it.

After all, “the horrible thing about the Two Minutes Hate was not that one was obliged to act a part, but, on the contrary, that it was impossible to avoid joining in.”