The immigration dilemma: how do immigrants impact Liberty?

May 11, 2017

On January 27, 2017, President Trump first issued an executive order temporarily suspending immigration from seven predominantly Muslim countries. People from across the political spectrum have weighed in on this policy: supporters claim that the executive order protects American security, while opponents believe that it unfairly targets certain groups. Regardless of opinions, this debate has brought attention to immigrants nationwide. How does immigration affect students? And how should Liberty respond to the growing tensions surrounding immigrants? Join the Patriot Press as we explore the circumstances and impacts of immigration for Liberty students.

What challenges do immigrants face?

Picture this: You have lived your entire life in a foreign country, but the promise of a better life leads you to America, intent to make it your home. You experience a sense of wonder at this new world, but also of loneliness. Uprooted from your old life, you miss your friends and routines back home. You feel surrounded, almost smothered, by strangers speaking a perplexing new language. Feeling completely alone, you wonder if this isolation will ever fade, if you will ever truly belong.

According to English Language Development teacher Andrea Antrim, finding a sense of belonging is often a challenge for immigrant students; for these students, this distressing scenario is a reality.

“When students immigrate to the United States, they are leaving behind their entire support base—friends, family, community—and coming to an area where they know no one,” Antrim said. “This is emotionally and mentally taxing on students. The pressure can be detrimental to their school work and health.”

Whether it’s settling into different schedules or adapting to unfamiliar customs, moving to a new country can be a hectic process. Oftentimes, immigrants experience economic hardships upon arrival, like for junior Ben Matsche, who emigrated from a small village in Germany in fourth grade.

“When we first came to America and bought our café, we were absolutely dead broke. I remember every morning I would get up at 6 o’clock and make a fire in the house so it was warm when my parents got up,” Matsche said. “In my house in Forks, we never had running water.”

Senior Nicole Leung, whose parents emigrated from Hong Kong, also notes the trade-offs for immigrants seeking opportunities in America.

“There’s a lot of sacrifice when your parents are immigrants. My dad used to have a white-collar job at a law firm in Hong Kong, but he decided to move here because he thought the education was better. In doing so, he lost that good job,” Leung said. “For parents who aren’t wealthy, they don’t actually get to live the American Dream, so the most they can do is set up their kids to live it.”

In addition to economic struggles, immigrants who do not speak English may experience problems communicating with others. This was the case for sophomore Melanie Zhgenti, whose parents emigrated from Turkmenistan.

“My first language was Russian, and that impacted me because once I got into primary school, I didn’t know any English. People would make fun of me or they wouldn’t talk to me because they thought I was weird,” Zhgenti said.

Matsche agrees, explaining that the language barrier can make it more difficult for student immigrants to develop peer relationships.

“Getting friends was difficult. For the longest time, I didn’t know what ‘Tag’ was in English. I always wanted to play a game, but we never had anything to play, and I didn’t know what it was called,” Matsche said.

Sophomore Sam Carvalho, who lived in France for 18 months, found that the language barrier significantly affected her parents. This put added pressure on Carvalho as she became the translator for her family.

“The most difficult part was having to speak for my parents. They learned the language much slower than I did, so I had to take on their role and communicate with other adults,” Carvalho said. “They would send up the seven year old to the bank to say that they needed money.”

This barrier is exacerbated, Antrim notes, when schools do not accommodate for students who speak other languages.

“We need more materials in a variety of languages,” Antrim said. “Imagine trying to fill out all of the sports registration information in a different language. If we want immigrants to participate in activities, we need to make them more accessible.”

In addition to adjusting to new languages, immigrants face misconceptions about their home countries. Zhgenti has been faced with many stereotypes based on her eastern European background.

“People think that I’m a communist or I drink vodka or I’m an alcoholic,” Zhgenti said.

As a German immigrant, Matsche has also experienced stereotypes in the United States.

“We went to a fair once, and there was a kid who came up to my mom and said, ‘Oh look, it’s that family. It’s the Nazis,’” Matsche said. “For a long time I would be called a Nazi.”

How does immigration impact Liberty students?

Though the processes of immigrating and adjusting to American society can be difficult, many student immigrants agree that the results are worth the hardships.

“Living in the United States is going to give me more opportunities than I would ever have living in Germany,” Matsche said. “Immigration is a wonderful thing. People can better their lives in America beyond anything in many other countries.”

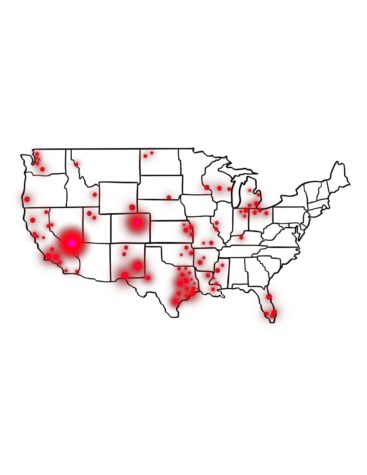

According to a recent survey of 268 students, only 3% of them are immigrants themselves. However, 28% of Patriots have at least one parents who is an immigrant. These students say that their families often develop a balance between preserving traditions and assimilating into American society. For junior Grace Lee, whose parents emigrated from South Korea, strong cultural connections are a major part of her life at home.

“My parents impose the Korean culture on their kids a lot more than if they were born here,” Lee said. “I can speak and understand Korean. Things like the culture, the rules, and bowing when you’re greeting older people are really stressed in our family.”

Along with exposing students to cultures other than a traditional American one, Carvalho notes that immigration can also change people’s viewpoints, making them more accepting of different people.

“Moving gave me a better perspective of people in other countries and what they go through. Especially for students who come from different countries and don’t speak the language, I empathize with them a lot more,” Carvalho said.

In light of today’s political climate, this idea of empathy is especially relevant. For junior Rianna Belaire, whose mother emigrated from Burma, being the child of an immigrant has given her a unique perspective on current events.

“I know that some of the people who are moving to America now are in the same place that my mom was in. There are so many opportunities that my family wouldn’t have if there was a ban on Burmese people,” Belaire said. “It hurts me seeing people who want to be after those same opportunities and not being able to because people are scared of them.”

How we can be more accepting of immigrants?

Political opinions aside, we can still learn to accept the immigrants we encounter in our personal lives. Freshman Amelia Hei, who was adopted from Cambodia, emphasizes the need for tolerance.

“I think it’s important for people to accept immigrants because you don’t know what background they’re coming from,” Hei said. “You don’t know their hardships or where they’re escaping from.”

Sophomore Tina Bardot encourages Patriots to consider their shared background as immigrants. Bardot immigrated to the United States from Belgium nine years ago.

“We need to understand that America is built on immigrants. Unless you are one hundred percent Native American, there’s no way that you or your family did not immigrate at some point,” Bardot said. “Deciding that you’re better than someone, or you belong here more, just because you’ve been here longer doesn’t make sense.”

According to social studies teacher Peter Kurtz, intolerance towards immigrants can stem from a lack of understanding.

“I know that fear motivates us, and the problem with fear is the unknown. So we should know more about immigrants,” Kurtz said. “I think we can be more accepting of immigrants by having those conversations.”

In order to foster acceptance, Antrim suggests that Patriots make an effort to interact with immigrant students.

“Students should try to get to know the immigrant students in their classes,” Antrim said. “You don’t need to ‘dumb down’ your English or speak extremely loudly or slowly. Just be clear with your speech. Be willing for conversations to be slower and have more pauses as the students process what you said, translate it into their native language, formulate a response, translate that response into English, and then share it with you.”

Overall, Leung recommends that people recognize their shared experiences with immigrants rather than focusing on differences.

“Immigrants are a lot more similar to natural-born citizens than you think. They just want to go to school and have a job,” Leung said. “The only thing that’s different is where they were born.”